Sometimes the driest regulatory reports reveal insights that make you chuckle—or raise your eyebrows. The latest European Central Bank Financial Stability Review is a case in point, highlighting a quirk that gives European banks a structural edge in the short-term dollar funding market, thanks to a regulatory loophole.

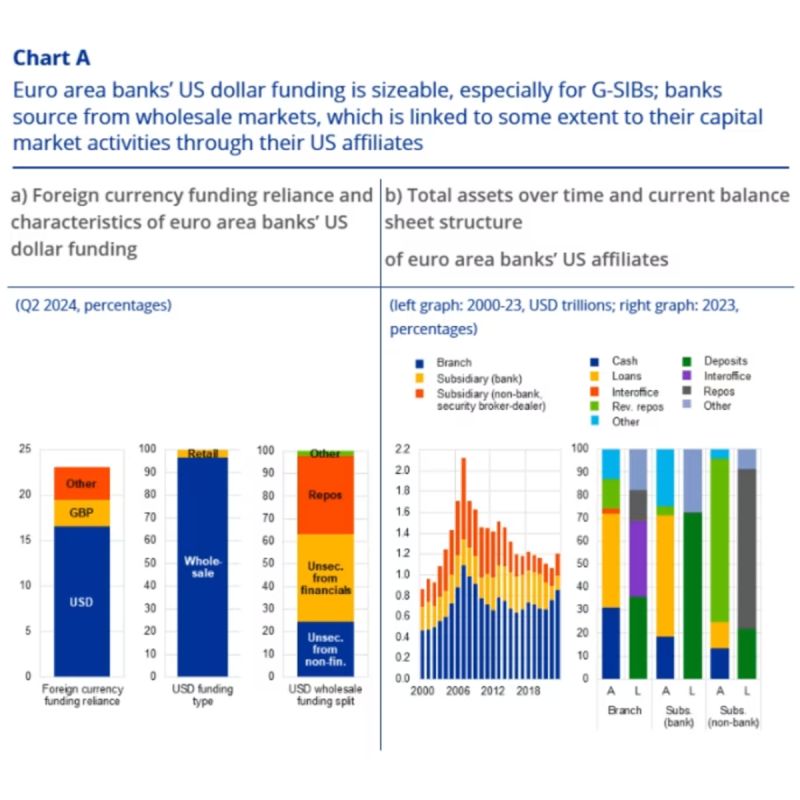

European banks, by tweaking their balance sheets to look sleeker at quarter-end, can engage in repo transactions with less capital than their U.S. counterparts. On top of that, these repo activities don’t inflate their deposit insurance premiums as they would in the U.S., creating a double advantage. But why don’t these European players dominate the dollar money markets?

The answer: déjà vu.

Back in the 2000s, European banks did dominate the USD money market, leveraging arbitrage opportunities where U.S. institutions couldn’t. By raising dollars from U.S. money-market funds at rates below the Fed’s interest on excess reserves, some European banks were pocketing eye-watering profits—until the 2011 Eurozone crisis exposed the fragility of these trades. When U.S. money-market funds questioned their high exposure to European banks, funding dried up overnight, triggering a scramble to exit what had become an unsustainable strategy.

Now, history might be repeating itself. After years of reduced U.S. activity, euro-area banks are back. Balance sheets of European broker-dealer subsidiaries in the U.S. are swelling again, with French banks leading the charge. Much of this borrowing fuels non-bank financial institutions, with banks effectively acting as intermediaries in the global dollar liquidity chain.

The ECB is rightfully concerned. A few systemically important institutions are diving deep into this high-stakes game of maturity transformation, shadow banking, and dollar funding—all underpinned by a regulatory quirk that feels almost too absurd to be true.

The question isn’t just whether these banks can outcompete U.S. rivals but whether the risks lurking beneath could lead to another crisis. History shows us that the market rarely tolerates this kind of imbalance for long.

Are we watching a clever arbitrage strategy—or the seeds of the next financial storm?

At SecFin Solutions, Glenn Handley epitomises expertise and innovation in global finance and management consulting.

Sign up to hear about our services and stay updated with the latest insights. Please enter your email address.

Access Specialised Training and Consulting Services Designed to Boost Your Financial Acumen and Success